|

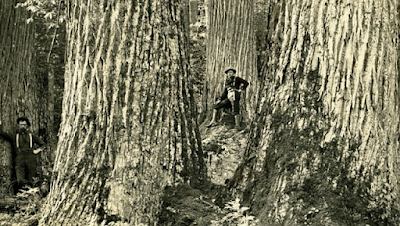

| A century old chestnut stump Author's Photo |

"Now you see it, now you don't!" is a phrase that often accompanies a stage magician's vanishing act. A card or coin is visible one moment and if by magic, disappears the next. At the end of the act, the object reappears much to the amusement and disbelief of the crowd. However, no magician could match the vanishing act that occurred in the early 20th Century. Instead of a coin or card, a much beloved symbol of the forests and landscape, the American chestnut, vanished and no amount of magic could bring it back.

The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) was heralded as the most perfect tree. Chestnut trees grew rapidly and achieved the status of one of the largest in the eastern woods. It has been estimated that chestnuts comprised 1 out of every 4 and sometimes even 1 out of every 2 trees in select regions across its native range from Maine to Mississippi.

|

| A pre-blight photo showing just how massive the American Chestnut could become Photo Retrieved From:https://www.usda.gov |

It was a tree that could sustain life from beginning to end. Wood from the chestnut was easily worked, yet was very strong, making it well suited for anything ranging from baby cradles to caskets. It was also remarkably rot resistant and thus perfect for key structural components of homes and barns. Bark from the tree was rich in tannins and used by tanneries to produce leather goods.

Perhaps the tree's most treasured asset was its delicious nuts hidden within spikey green burrs. Smaller but sweeter than its European or Asian cousins, the American chestnut was considered the most palatable nut in the eastern woods. Its crop was the most consistent of the nut producing trees and with the arrival of each fall, the burrs would open and release 3 to 4 chestnuts.

Perhaps the tree's most treasured asset was its delicious nuts hidden within spikey green burrs. Smaller but sweeter than its European or Asian cousins, the American chestnut was considered the most palatable nut in the eastern woods. Its crop was the most consistent of the nut producing trees and with the arrival of each fall, the burrs would open and release 3 to 4 chestnuts.

Locals would flock to the woods to gather them by the wagon load for personal consumption, livestock feed, or to sell for profit. Chestnuts were also a favorite of bears, turkeys, deer, birds, and other forest dwellers. Even before the last glaciers retreated from the continental United States, the American chestnut fulfilled this nurturing role. No one could have imagined that it would essentially disappear in less than one human lifetime.

In 1904, American chestnuts growing at the Bronx Botanical Garden in New York City were found to be afflicted with a disease that produced orange cankers and defoliated the branches. Not long after, other chestnut trees growing around New York City exhibited the same symptoms. Within two to three years, infected trees were dead or dying. The disease confounded biologists at first as to its cause, but it was soon determined to be the work of Cryphonectria parasitica, a fungus whose spores killed the tree's living tissue by producing acid leeching cankers.

|

| Cankers caused by the fungus Photo Retrieved From:https://acf.org/ |

The fungus had unknowingly arrived in the United States attached to imported oriental chestnuts. These trees had coevolved with the fungus for thousands of years and as a result, developed an immunity where few trees were killed outright. The American chestnut on the other hand, being a continent and an ocean away had never interacted with it. When they met, what transpired proved to be one of the worst ecological disasters to strike the world's forests.

|

| Chinese Chestnut leaves and catkins. Leaves are more ovular and shiny compared to American chestnuts. Photo Retrieved From:https://upload.wikimedia.org |

To analyze the impact and the subsequent demise of the American Chestnut in Central PA, I've chosen to focus on information derived from newspaper articles regarding chestnuts before, during, and after the blight. The fact that chestnuts were routinely written about in the newspaper demonstrates just how important their existence was.

Falling within its natural range, the American chestnut was well represented in Central Pennsylvania. Trees of considerable size once grew within the region as evident by an article in the Democratic Watchmen. It announced that a chestnut tree had been cut and that the diameter at stump level was 5ft. 11in. To gaze upon one of these "Appalachian Redwoods" must have quite an experience.

"Chestnutting", the act of collecting chestnuts, was a pastime now lost upon younger generations. For those who grew up with these amazing trees, it was a much-anticipated event every fall. Area newspapers would often try to predict how bountiful the upcoming chestnut crop would be and later report on the condition of the crop once the nuts began falling.

Not everyone was excited for chestnutting to begin. As one resident of Lemont wrote in the Democratic Watchman in October 1903, "It appears there is no law or no officers in these parts, for while the chestnut crop lasts neither Sabbath law or trespass law are regarded." It was also around this time that Sunday school attendance began to drop as children joined their parents in the search for the delicious nuts.

While chestnuts were a coveted treat, they also provided a cash crop for local residents. Bushels by the wagon load were taken to local railroad stations for shipment to metropolitan markets in the east. In 1892, the Centre Reporter of Centre Hall remarked that valley residents had sold chestnuts to eastern markets for 40 cents a bushel, or roughly $12 dollars in today's money.

Chestnuts had also intertwined themselves into social affairs. Chestnut parties were a popular social event of the era. A popular party game was the "chestnut conversation" where each participant roasted a chestnut over an open fire. When a person's chestnut popped open, they were obligated to tell a story of which the oldest and most enjoyable tale was deemed the winner. Another game was a bit like curling where a tablecloth was stretched over table and marked from 0 to 100. Players took turns flicking chestnuts across the table with the goal of racking up the most points scored from chestnuts landing on the marked areas.

Chestnuts had also intertwined themselves into social affairs. Chestnut parties were a popular social event of the era. A popular party game was the "chestnut conversation" where each participant roasted a chestnut over an open fire. When a person's chestnut popped open, they were obligated to tell a story of which the oldest and most enjoyable tale was deemed the winner. Another game was a bit like curling where a tablecloth was stretched over table and marked from 0 to 100. Players took turns flicking chestnuts across the table with the goal of racking up the most points scored from chestnuts landing on the marked areas.

Unrealized by many, the blight was advancing rapidly towards them. Spores could be carried by the wind, insects, birds, wildlife, and by humans through the transport of infected logs or logging equipment. In New York and New Jersey the disease was shown to be capable of spreading 50 miles or more in just a year.

As expected, the blight soon arrived in Pennsylvania. Chestnut trees near Haverford in Montgomery County were found to have been infected by the blight in 1908, four years after its discovery in New York. Just a year later, the Montour American of Danville reported the blight had arrived in Northumberland County, covering the nearly 100-mile distance in less than a year's time. With a seemingly unstoppable conflagration approaching them, residents west of the Susquehanna River could only hope that it would somehow be extinguished before reaching their homes and forests.

|

| A chestnut tree near Philadelphia infected by the blight. Notice the dead branch. Pennsylvania Chestnut Blight Commission |

On June 14, 1911, the state legislature passed a bill formally establishing the Pennsylvania Chestnut Blight Commission whose mission was to analyze the extent of the blight, educate the public, and limit its spread through science and practical means. To accomplish the latter, $275,000 ($7.6 million in today's dollars) were appropriated to the commission. To limit the spread of the blight, the commission adopted a strategy of finding and destroying as many infected and sometimes uninfected trees as possible.

|

| A Chestnut Blight Commission map showing the distribution of the blight in regards to the tree's native range |

Those in the scientific community disagreed; it was argued that the spread of the blight was beyond human control and that attempts to control or eradicate it would only be a waste of money and resources. Nevertheless, the commission continued with their plan with the idea that doing something was better than nothing. Two management districts were established, East and West, divided on a line running along the eastern boundaries of Fulton, Huntingdon, Mifflin, Centre, Clinton, Sullivan, and Bradford counties.

As per commission guidelines, destroying a diseased tree began with felling it as close to ground level as possible. Once cut, the bark of the main trunk is peeled off along with any bark on the stump. The bark, limbs, brush, and fallen leaves are then piled onto the stump and burned. Wood that was to be utilized for outdoor use such as fences or rails had to be peeled. If used for firewood and kept undercover, peeling was not required. Wood from the tree could be transported by rail but only in closed boxcars.

As per commission guidelines, destroying a diseased tree began with felling it as close to ground level as possible. Once cut, the bark of the main trunk is peeled off along with any bark on the stump. The bark, limbs, brush, and fallen leaves are then piled onto the stump and burned. Wood that was to be utilized for outdoor use such as fences or rails had to be peeled. If used for firewood and kept undercover, peeling was not required. Wood from the tree could be transported by rail but only in closed boxcars.

In the east, which included Union and Mifflin counties, the disease was already well established. Agents of the commission did not force landowners to cut their diseased chestnuts unless they were within a half mile of a chestnut orchard or nursery. However, agents still encouraged landowners to cut both diseased and sound chestnuts to utilize their maximum timber value and reduce transmission to the western zone. It was already too late for the eastern zone.

|

| Blight Commission agents removing bark from diseased chestnuts Photo Retrieved From: https://www.pennlive.com/news/2017/10/american_chestnut_chestnut_bli.html |

In the Western Zone, the blight had not yet been seen in significance. It was believed that if any pockets of blight could be found and destroyed promptly, the Western District could be spared from devastation. Agents of the commission would utilize a more stronghanded approach. Infected trees would be marked, and agents would then dictate to landowners the proper method to destroy the high-risk parts of the tree, of which they had twenty days to do so. Failure to cut the diseased trees within that time would result in agents of the commission coming onto the property and doing so themselves with a bill for services presented to the landowner.

By December of 1911 foresters with the blight commission arrived in Centre County to assist landowners with recognizing and reporting blight infected trees as well as searching for blighted trees in the region's forests. The article stated that the foresters would remain throughout the winter and would be headquartered in the Brockerhoff House in Bellefonte.

By December of 1911 foresters with the blight commission arrived in Centre County to assist landowners with recognizing and reporting blight infected trees as well as searching for blighted trees in the region's forests. The article stated that the foresters would remain throughout the winter and would be headquartered in the Brockerhoff House in Bellefonte.

Less than a month later, the men discovered an isolated section of blighted trees on Muncy Mountain (Bald Eagle Mountain) near the Haupt Farm. The article then reports that the men were being relocated to Port Matilda to investigate possible reports of blighted trees between there and Tyrone. Additional blight infestations were confirmed by the end of the year near Paddy Mountain and within the Seven Mountains.

Neighboring counties were not fairing any better. Blight had been found near Altoona in Blair County, Clearfield in Clearfield County; between Bellville and McVeytown in Mifflin County; in Sugar Valley in Clinton County; and throughout Union, Synder, and southern Lycoming counties. Though these outbreaks were small, it was becoming clear just how widespread the disease was becoming.

Neighboring counties were not fairing any better. Blight had been found near Altoona in Blair County, Clearfield in Clearfield County; between Bellville and McVeytown in Mifflin County; in Sugar Valley in Clinton County; and throughout Union, Synder, and southern Lycoming counties. Though these outbreaks were small, it was becoming clear just how widespread the disease was becoming.

|

| An article in the Democratic Watchman in November 1912 |

Work in Centre County continued into the next year. According to an article published in the Democratic Watchman, foresters had discovered pockets of blighted trees in Snow Shoe, Union, and Howard townships, but reported that "little damage had been done." The author expressed hope that the disease could still be stamped out in the county before too long.

Further attention was directed towards the blight during the Centre Hall Grange Encampment in September 1912, now affectionately called The Grange Fair. The Blight Commission announced in the Democratic Watchman that it would be displaying an exhibit at the fair accompanied by an experienced forester who could explain the disease to the public. Specimens of the blight in each of its stages were to be displayed. The author closed the article by hoping that "a large number of people will take advantage of this opportunity to save their chestnut trees by learning how to combat this new and serious enemy."

Regardless of these efforts, the enemy was quickly gaining a foothold in the region. By late September 1912 pockets of blight had been confirmed near Howard, Snow Shoe, Unionville, Philipsburg, Houtzdale, Stormstown, Boalsburg, and Pine Grove Mills. It was found that the blight had made considerable headway in Huntingdon County near Orbisonia and along the southern Centre County line. By November that same year, Rebersburg was added to the list when over 150 trees on Brush Mountain were found to be suffering from the blight.

In 1914, the Pennsylvania Chestnut Commission was dissolved after achieving negligible results. By the end of its lifespan, the commission located 37,510 diseased trees and cut 30,705 of them.

Though the blight marched on, newspapers continued to report on the season's chestnut crop, which appeared to be quite plentiful for the next several years. This may be attributed to the fact that trees infected with the blight, sensing their imminent demise, produced bumper crops of chestnuts in the hope to continue their linage in the next generation.

The year 1920 seemed to be when the wheels finally fell off the wagon. Newspapers that had once reported on the bountiful chestnut crops were now saying that not a chestnut could be had. Salvaging efforts initiated the year before by the state forestry department continued and expanded. It was also the year when significant outbreaks of blight were found in the Northern Tier counties of Potter, Tioga and Warren. An article in the Democratic Watchman hypothesized that the chestnut tree in Pennsylvania would be extinct within five years and that financial loss of the chestnut to the state totaled more than $60,000,000.

The year 1920 seemed to be when the wheels finally fell off the wagon. Newspapers that had once reported on the bountiful chestnut crops were now saying that not a chestnut could be had. Salvaging efforts initiated the year before by the state forestry department continued and expanded. It was also the year when significant outbreaks of blight were found in the Northern Tier counties of Potter, Tioga and Warren. An article in the Democratic Watchman hypothesized that the chestnut tree in Pennsylvania would be extinct within five years and that financial loss of the chestnut to the state totaled more than $60,000,000.

Throughout the 1920's, chestnut was salvaged in an attempt to recoup some of its value in timber and to reduce dry fuels that could feed a potential forest fires. Larger trees would be used for lumber, smaller ones for fence or utility poles. Advertisements in local papers announcing the sale of chestnut props and fence posts became common.

|

| An advertisement for chestnut posts in the Democratic Watchman in 1921 |

By the 1930's American chestnut was virtually extinct in Pennsylvania, with its destructive deed complete, it moved south to continue its carnage. Before the blight struck, it was estimated that 4 billion chestnut trees grew across the eastern United States. By the 1950's the tree was functionally extinct from its native range.

However the hearty chestnut would not disappear entirely. Aboveground, trees had no defense against the fungus, however microorganisms in the soil could destroy it. Thanks to this defense, younger trees that were killed by the blight still had the ability to stump sprout in an attempt to regrow itself. Unfortunately, the fungus was here to stay. Though it primarily targets chestnut trees, the fungus could survive and reproduce in the bark of other tree species, especially oaks, without harming them. Chestnut trees rarely reach nut bearing maturity before being killed off, only for the roots to send up new shoots to begin the cycle again.

Over a century later several survivors have been found scattered around the state, mainly in the north-central region. One tree found by the author in Clinton County has reached an impressive height of 50ft. or so and is producing chestnuts. So far, no sign of blight is visible. However, not too far away are the rotting remnants of trees killed by the blight a century ago. For now, this tree has escaped this fate.

|

| The tree has reached the canopy and appears healthy. A younger offshoot of the same root system can be seen in the upper right. Author's Photo |

|

| The rotting remnants of a long gone chestnut Author's Photo |

Information Retrieved From:

Coming Soon!

Thank you for the info. My father often told me about the Blight.

ReplyDelete